The Silent Crisis of Mission Drift

I recently read an outstanding leadership book on the topic of Mission and what can happen when an organization’s leaders let it drift.

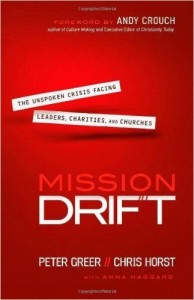

The book is called Mission Drift

The book is called Mission Drift, written by Peter Greer and Chris Horst. As the president and director of development respectively for HOPE International, a global nonprofit focused on addressing both physical and spiritual poverty through microfinance, Greer and Horst share what they’ve learned on staying Mission True.

In the book, the authors specifically focus on Christian organizations, reflected by the subtitle, ”The Unspoken Crisis Facing Leaders, Charities, and Churches”. However, anyone passionate about the mission of their organization can learn much from this book.

It’s not uncommon for the founders of an organization – either for-profit or not-for-profit – to be crystal clear about their mission and the purpose of their organization. Their #1 desire is to see the mission fulfilled for as long as the need, problem, or crisis exists – or for as long as God permits the organization to serve.

Organizations that consistently stay true to their mission are what the authors call Mission True, which they define as follows:

Mission True organizations know why they exist and protect their core at all costs. They remain faithful to what they believe God has entrusted them to do. They define what is immutable: their values and purposes, their DNA, their heart and soul.

Sadly, there are many organizations that have experienced mission drift, which the authors refer to as Mission Untrue.

Examples of Mission Drift

Over time, when new leaders assume control of an organization, changes are made that threaten the original mission. Drift occurs little by little, and then all of a sudden an organization is focused on something that looks nothing like the original mission.

Over time, when new leaders assume control of an organization, changes are made that threaten the original mission. Drift occurs little by little, and then all of a sudden an organization is focused on something that looks nothing like the original mission.

Greer and Horst highlight a number of organizations that have drifted far from their founders’ original mission, including:

- World-renowned Harvard University, founded in 1636, originally only employed Christian professors. Their focus was on fulfilling the stated mission of instructing students to “know God and Jesus Christ.” But today this school has no ties to its Christian roots. In 1987 the president of the university acknowledged the school had strayed far from its original mission, becoming a completely secular university, with no option of turning back.

- Howard Pew and his family were strong Christians. The Pew family made a lot of money in the oil business. When they desired to be generous with their wealth, they set up a foundation that ultimately became the Pew Charitable Trusts. Howard Pew wanted all donations to only be made to organizations that were faithful to the Gospel (e.g. Billy Graham’s evangelical ministry). But after the founder died, this charitable foundation drifted significantly, funding organizations that Howard Pew and his family would never have approved, such as Planned Parenthood and many Ivy League schools.

- George Williams first started the Young Man’s Christian Association (YMCA) as a Bible study for displaced men in London, England. The core of this group was centered on learning about Christ, eventually training and commissioning over 20,000 missionaries. But as the organization grew and expanded to other countries, the focus became all about health and fitness with no reference to Christ. In 2010, the organization officially dropped three of its four letters to become simply The Y, removing any remaining ties to its Christian roots.

Now, many will look at these organizations and say there is nothing wrong with where they ended up. These are reputable and well-respected organizations doing good work.

But the truth is they are no longer fulfilling their original mission.

The BIG Question

To those who have ever experienced a clear sense of purpose, a shift in mission is considered a slap in the face. All honor is lost.

As a founder, you might think future organizational leaders will appreciate or at least honor your passion and purpose. But unless they share the same passion for the mission, be prepared for mission drift. It’s not uncommon for new leaders to be open to shifting the mission, providing the organization continues to experience success. As long as the organization is still doing something worthwhile, providing employment, and/or showing a reasonable return on investment, then everything is acceptable.

As a founder, you might think future organizational leaders will appreciate or at least honor your passion and purpose. But unless they share the same passion for the mission, be prepared for mission drift. It’s not uncommon for new leaders to be open to shifting the mission, providing the organization continues to experience success. As long as the organization is still doing something worthwhile, providing employment, and/or showing a reasonable return on investment, then everything is acceptable.

Why change?

Such leaders believe they must continually adapt to societal, cultural, governmental, and/or technological pressures just to survive. They believe that as the world changes, so does an organization’s purpose.

Well…. as Phil Vischer states so clearly in his book, Me, Myself, and Bob, this is how organizations become amoral – lacking any kind of moral sense. When leaders allow an organization to blow with the wind, it risks becoming values-less.

This leads us to a very important question:

Should the mission of an organization ever be changed?

According to Greer and Horst, the answer is NO.

I agree. In fact, through my research of Fortune 500 companies (American-based companies with annual revenue exceeding US $5.1 Billion in 2016), I’ve been surprised at the number of big companies that have disappeared over the past few years. They may have merged with or sold out to another company, but I believe a common reason for the change was the loss of focus and/or an uninspiring mission.

The lack of clarity around purpose and being intentional about mission has been the downfall of thousands of organizations, some very large. Instead, they become the fodder for case studies and business books.

Remaining Mission True

Greer and Horst argue that remaining Mission True is not only morally right, it can also lead to significant growth.

Greer and Horst argue that remaining Mission True is not only morally right, it can also lead to significant growth.

As a good example, the authors tell the story of the charitable organization Feed My Starving Children (FMSC). After years of putting “a nice secular face on the organization”, the leaders of FMSC decided to rededicate the organization to its Christian roots in 2003. The results since then have been stunning, with many new donors stepping up to support the mission. Over a nine year period, FMSC saw its annual budget increase 42 times, from $830,000 to over $35 million!

Of course, not every organization will see such growth. But Mission True organizations often experience the unexpected, with new doors opening for them where they never thought possible. Why? Because donors, customers, employees, volunteers, investors, and more appreciate clarity of focus.

In addition to the success experienced by FMSC, the authors highlight a number of organizations that have remained Mission True over a long period of time, including:

- Taylor University, a small Christian college in Indiana, was founded in 1846. It has remained true to its mission for over 150 years, and ranked #1 in the category of Best Regional Colleges for five years in a row. As Dr. Ben Sells, VP of Advancement, is quoted in the book as saying, “Our challenge going forward is to be more true to who we are than we’ve ever been before.” The leaders of this school wake up every day focused on how to protect and live out its mission.

- The Crowell Trust was established by Henry Crowell, the founder of Quaker Oats Company. Crowell was an active Christian who helped rid Chicago of its Red Light District in the early 1900s. When he set up his Trust, he ensured that all of his wealth would go only to those causes he would approve of, namely “…such institutions only as are loyal to the [Christian] faith.” Today, the trustees work from the same charter and support the same mission as when it was first written.

- InterVarsity was started by a group of British students in 1877 at the University of Cambridge. This group expanded globally to share the Gospel with students on nearly 600 campuses. In spite of significant challenges – including being expelled from various campuses – the focus and activities of this organization today would make it’s founders proud.

Such organizations are well respected for their clear focus on their purpose, and the difference they have made in thousands of lives.

Does this mean they are rigid and never change? Should change be viewed as bad or that organizations shouldn’t adapt?

Being Adaptive to Change AND Mission True

The authors nicely outline the difference between the need for an organization to be adaptive to change and staying Mission True.

While it’s easy to label all changes as drift, sometimes change is necessary to stay on mission. Being Mission True isn’t synonymous with being unchanging. On the contrary, remaining Mission True will demand you change to continue to fulfill your mission.

In other words, change and adaptation are fine as long as the core identity of the organization is not altered. This may be the reason why organizations first established core values – defining the few immutable qualities that were aligned with the mission.

So, in a world that’s changing faster than ever, how do leaders stay Mission True?

Greer and Horst outline three important factors:

- Mission True organizations know why they exist.

- Mission True organizations differentiate means from mission.

- Mission True organizations change to reinforce their core mission.

Bottom line: an organization’s leaders need to be aware that the pressures for mission drift are strong and never stop. Remaining Mission True requires leaders who continually revisit the organizational history and the reason the organization exists. It also requires leaders who are flexible with strategic planning but remain stubborn about their mission, vision, and values.